Americans drink more than 1 billion glasses of drinking water per day, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). And, while adults are drinking more water than before, we often take this colorless, odorless, and essential liquid for granted. The United States Geological Society (USGS) notes water composes 60% of our bodies — ensuring the proper functioning of our bodies and making the basic molecules of life, including DNA, cell membranes, and proteins, work.

However, more than 780 million people around the world lack access to clean drinking water, per a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clean water is even considered a relatively recent luxury in North America. In 1908, Jersey City, NJ was the first city to disinfect its drinking water, with thousands of cities following Jersey City’s lead during the next decade.

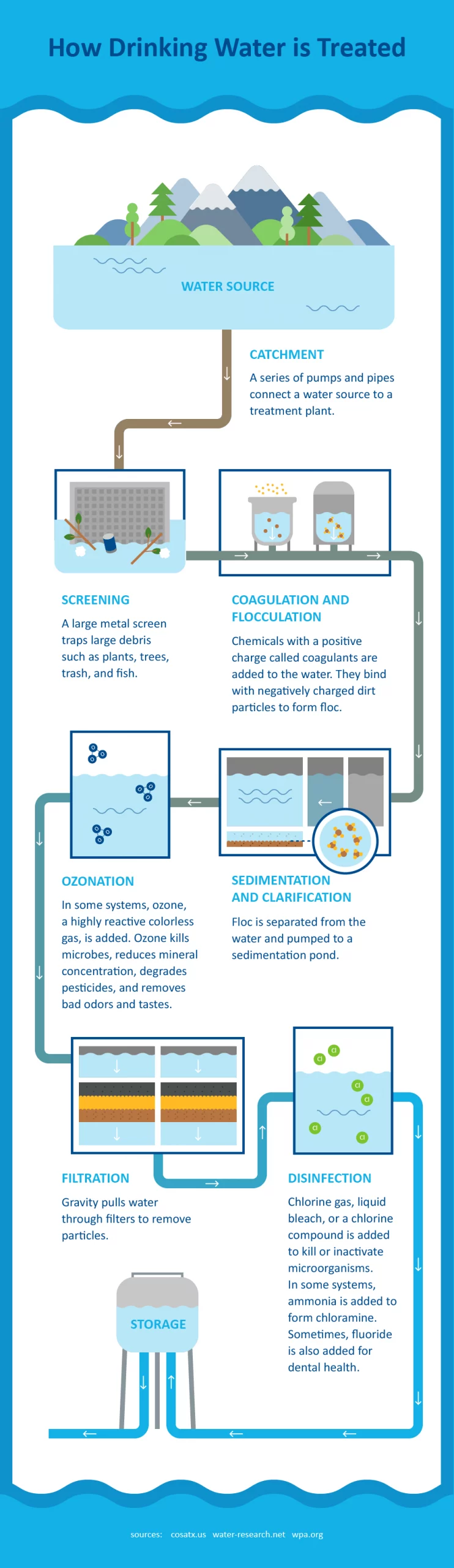

Today, most Americans have access to a disinfected drinking water supply at home and the workplace. But, many aren’t aware of how municipal water treatment works before it reaches their glass. Read on to learn more about the treatment and distribution of the public water system and how workplaces can provide top-tier water quality for their employees, guests, and customers moving forward.

Drinking Water Sources and How They’re Treated

Water Sources

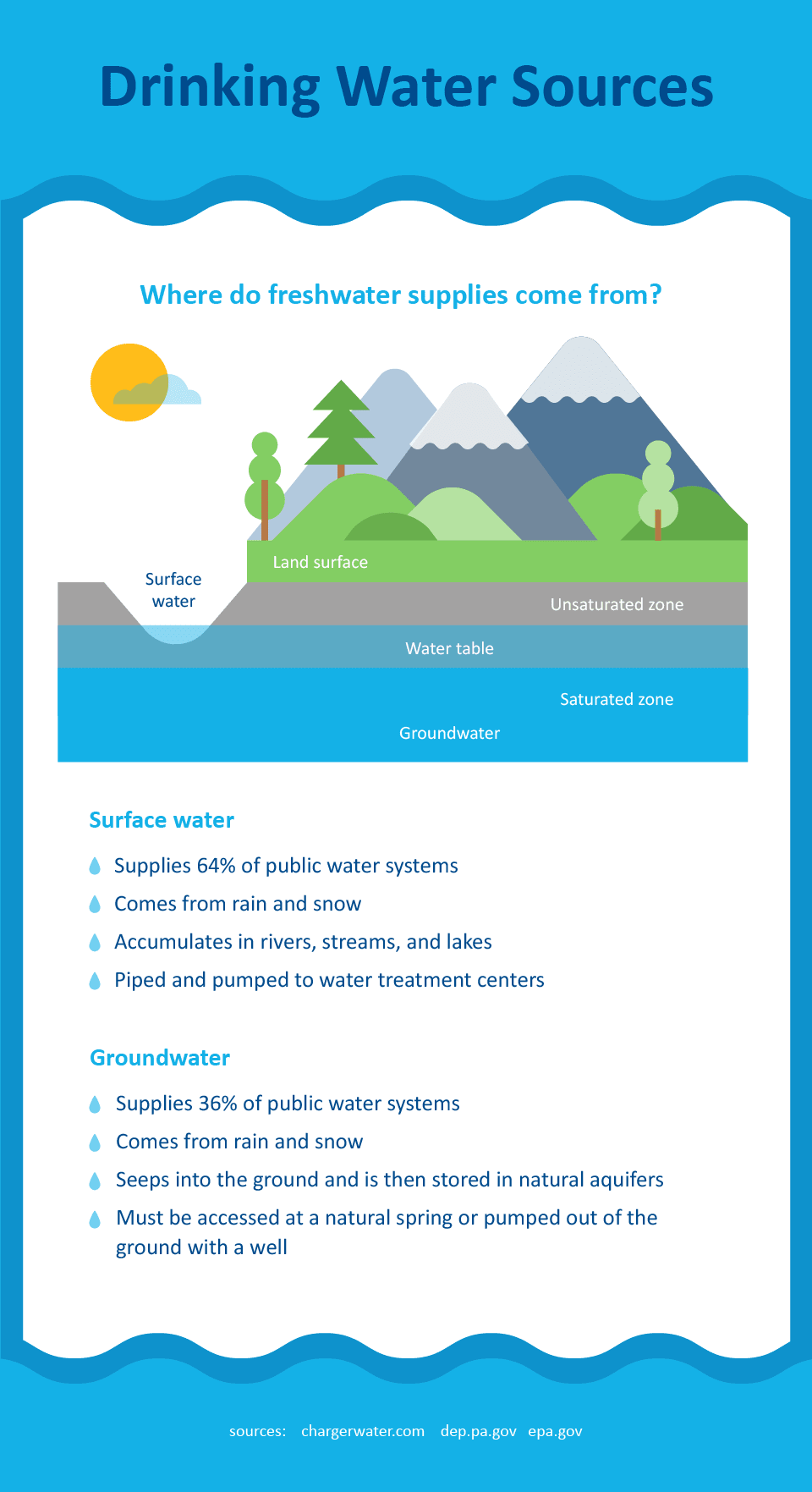

Source water refers to sources or bodies of water (such as rivers, streams, lakes, reservoirs, springs, and groundwater) that provide water to public drinking water supplies and private wells. Most U.S. tap water sources come from surface water or groundwater, per the CDC.

- Surface water: This is any water that originates from above ground, including streams, rivers, lakes, wetlands, reservoirs, and creeks.

- Groundwater: Groundwater, on the other hand, is the water underground in the cracks and spaces in soil, sand, and rock.

From Source To Tap

USGS highlights that the majority of our freshwater supply comes from surface water, and those water sources aren’t always nearby:

- The New York Times reports roughly 90% of New York city’s water comes from the Catskill/Delaware watershed, which extends 125 miles northwest of the city.

- Chicago’s water travels more than 100 miles from Lake Michigan.

- Atlanta’s water travels a couple of hundred miles upstream from the Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers.

- People in 7 states stretching from Denver to Los Angeles rely on drinking water from the Colorado River.

The rest of our freshwater comes from groundwater, which originates from rain and snow that seeps into the soil. It’s stored in aquifers, natural formations of soil, rocks, and sand beneath the ground. Groundwater is accessed from natural springs or pumped out of the ground by way of a well and is mainly used as drinking and irrigation water. While the majority of states are mainly supplied by surface water sources, Miami, Memphis, and San Antonio draw most of their water from groundwater because these locations have groundwater aquifers.

To learn more about where your municipal drinking water comes from, check out the EPA’s interactive drinking water map.

Taking a Closer Look at Drinking Water Distribution

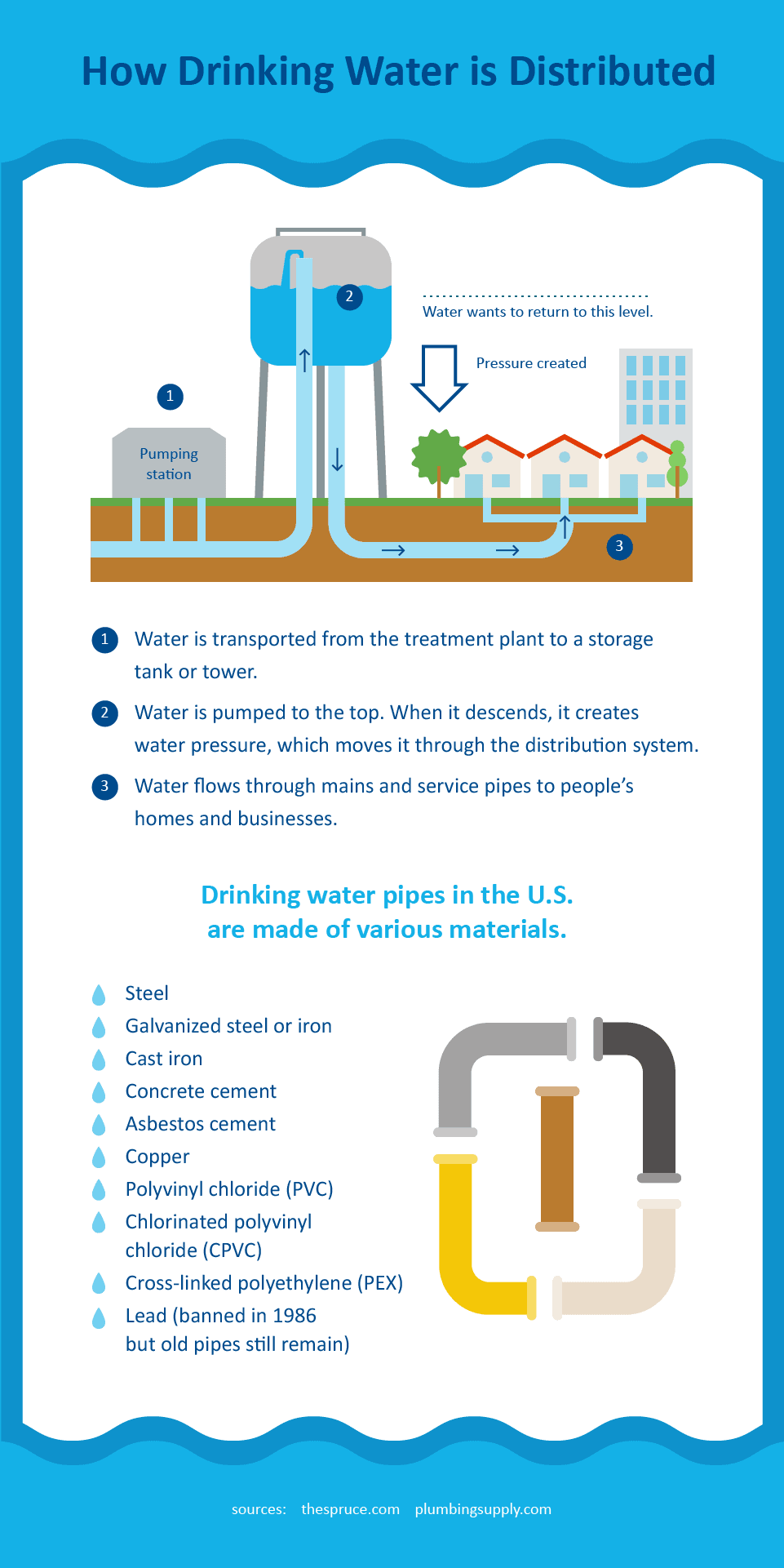

After drinking water is treated and meets the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Safe Drinking Water Standards, it’s transported to storage facilities where homes and businesses can access safe, clean drinking water straight from their taps. The EPA reports that American water distribution systems span nearly 1 million miles and deliver water to approximately 300 million people. Distribution systems are mostly underground and include:

- Pipes

- Control valves

- Pumps

- Meters

- Storage tanks

- Hydrants

Distribution systems must provide an adequate amount of water with sufficient pressure. Without pressure, water stands still. Pumping water to the top of a water tower or a water tank in a high location creates water pressure. When the water descends, it creates force, which in turn moves the water through the mains and pipes. Residential water pressure is usually kept between 45 and 80 pounds per square inch (psi).

The pipes that transport water can be made of several different materials. Some of the most common materials include:

- Steel: An alloy of iron and carbon, steel is the strongest and most durable material used for water supply pipes.

- Galvanized steel or iron: This type of pipe has a protective zinc coating to prevent rusting. Sustainable Sanitation and Water Management reports that the use of these materials is declining because pipes corrode over time — giving water an unpleasant taste and smell.

- Cast iron: This iron alloy is incredibly durable and has been used for water distribution pipes for hundreds of years.

- Concrete cement and asbestos cement: Concrete cement pipes are still used and tend to be resistant to erosion.

- Copper: A red-brown elemental metal, copper is lightweight, durable, and naturally corrosion-resistant. Research finds that copper pipes can leach small amounts of copper into the water, which can be harmful to individuals with certain medical conditions, including Wilson’s Disease.

- Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC): A rigid plastic, PVC is usually only used for cold water pipes because it breaks down when exposed to heat.

- Chlorinated Polyvinyl Chloride (CPVC): This type of plastic can withstand temperatures up to about 180℉ and is used for both hot and cold water pipes.

- Cross-linked Polyethylene (PEX): A lightweight, flexible, and inexpensive plastic, PEX is replacing copper and galvanized steel.

- Lead: This malleable elemental metal was used to make and solder pipes until Congress banned it in 1986 to prevent childhood lead poisoning. More than 10 million homes still get their water from older lead water service lines (the pipes that connect main service lines to a house’s plumbing system), according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

The Problem With Local Treatment and Distribution

Waterborne illnesses such as giardia, hepatitis A, typhoid, and cholera are real risks for residents and travelers who drink tap water in many parts of the world. In general, tap water in the U.S. is safe, but American water treatment and distribution systems aren’t perfect. Examples like the Flint, Michigan water crisis evidences this. In fact, the New York Times reports that about one-quarter of U.S. residents get their drinking water from sources that violate the EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Standards: Most are in low-income, rural areas. Even if water is deemed safe to drink when it leaves a treatment plant, pipes in aging distribution systems can contaminate it. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority notes that lead can also leach into water inside homes and businesses from old lead pipes or brass plumbing fixtures made before 2014.

Provide Clean Water at Work With a Bottleless Water Cooler

Because municipal tap water treatment and distribution aren’t always reliable, filtering water is the best way to ensure your workplace water is clean, safe, and delicious. Today, organizations are increasingly turning their attention to bottleless water dispensers that use advanced water filters to elevate their water supply. A bottleless water dispenser from Quench uses state-of-the-art filtration technology to provide crisp, clean, revitalizing alkaline water that tastes great and is more supportive of the well-being of your employees, guests, and customers. And our Quench Water Experts are here to ensure your water solutions are tailored to your local water supply.

Explore our broad range of bottleless water dispensers to find a machine that’s the right fit for your company’s water needs, and get a free quote to get started.